|

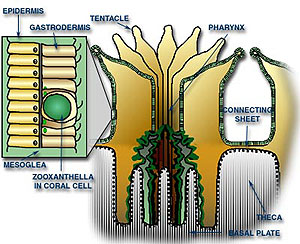

Size and form The individual polyp is a saclike animal with a

central mouth surrounded by a ring of tentacles. The opposite end is

called the base, and here the polyp attaches to the substrate. The size

of the individual polyp may vary considerably from less than a couple of

mm's to 20 cm's in diameter. Generally the larger species are solitary

soft corals, while most of the colonial stone corals are small. |

||

|

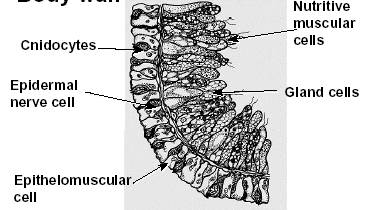

Nerves The polyp is a relatively simple animal, which

lack a brain but have a simple nervous system called a nerve net that

extends from the mouth to the tentacles. The polyp can detect chemical

substances in the surroundings (similar to our sense of taste and smell),

which aid the animal in sensing potential prey and danger from predators.

|

||

|

Nematocysts The polyp's tentacles are used to move food particles towards the mouth and for defense. The tentacles contain small stinging capsules (also called nematocysts), which contain a venom-filled thread with a minute barb at its tip. The nematocysts are triggered by physical or chemical stimulation, which results in the ejection of the thread. The barb then penetrates the victim's skin where the venom is released. |

|

||

|

Reefbuilders Reef-building corals are surrounded by a calcium carbonate skeleton. This skeleton is formed by the secretion of calcium carbonate on the outside of the coral polyp. The exact process by which the calcium carbonate skeleton is formed is not yet known, but it is assumed that the photosynthetic action of the zooxanthellae promotes the formation of the skeleton. The calcareous skeleton is continuously secreted, and when a polyp in a colony dies a new polyp will take its place, and build a new calcium carbonate skeleton on top of the old skeleton. This is why a coral reef, over a time span of thousands of years, can reach an impressive size (for example the Great Barrier Reef on the east-coast of Australia). |

|||